BY | DEC 30, 2009

“To see the Earth as it truly is, small and blue and beautiful in that eternal silence where it floats, is to see ourselves as riders on the Earth together, brothers on that bright loveliness in the eternal cold – brothers who know now they are truly brothers.” – Archibald MacLeish, Skull & Bonesman (and uncle of Bruce Dern, for you LC fans), reflecting on the alleged flight of Apollo 8

In the first of this series of posts, I mentioned that the Apollo story was connected to the Laurel Canyon story by way of a facility known as Lookout Mountain Laboratory, the intelligence community’s top-secret, state-of-the-art film studio nestled high in the Hollywood Hills. As it turns out, there is another interesting connection as well: during the span of precisely one month, during the infamous summer of 1969, the Laurel Canyon and Apollo stories reached a simultaneous climax, of sorts.

On July 16, 1969, Apollo 11, the flight that would allegedly land men on the Moon for the first time, took flight. Five days later, on July 21, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin allegedly first set foot on lunar soil. Three days later, the trio of Apollo astronauts triumphantly returned home to a hero’s welcome. Exactly one week later, the first letter from the so-called Zodiac killer was received by authorities. Eight days after that, on the night of August 8, 1969, Sharon Tate and four others were slaughtered in Roman Polanski’s Benedict Canyon home. The next night, Rosemary and Leno LaBianca were carved up in their Los Feliz home. All of these killings would later be attributed to canyon regular Charlie Manson and his Family. Less than a week after the killings, some of Laurel Canyon’s premier bands took the stage at Woodstock to celebrate the other side of the canyon scene.

It was a time of supreme weirdness, with extreme and very high-profile violence weaving its way through the flower-power scenes in both Los Angeles and San Francisco, while 234,000 miles away, squeaky-clean astronauts who bore little resemblance to members of the Woodstock generation allegedly beamed back live footage from the Moon.

Anyway, I think when we left off we were discussing the highly improbable flight of Apollo 8, the very first manned launch of a Saturn V, which took flight, as I previously mentioned, on the winter solstice of 1968. The mighty Apollo spacecraft, which had failed on its last unmanned outing, purportedly flew all the way to the Moon, did ten quick laps around Earth’s nearest neighbor, and then flew back home, with every one of its 9,000,000 parts performing flawlessly.

Thanks for that was due in part, according to the official Apollo legend, to a band of surfers in Seal Beach. North American Aviation, you see, had a bit of a problem with keeping the liquefied hydrogen and oxygen in the Saturn V’s second-stage from boiling in the Florida sun. The proposed solution was to insulate the fuel tanks with honeycomb insulation, but NASA’s engineers had trouble keeping the insulation from popping back off. The solution to that problem was to hire local surfers, who, according to Moon Machines, brought with them a “special skill set.”

NASA claimed, by the way, to shoot for 99.9% accuracy in the manufacture of its Apollo spacecraft, which shouldn’t have been a problem for a workforce composed of Nazi rocket scientists, bra seamstresses and surfers. Even if that lofty goal had been attained, however, that would still have left 9,000 defective parts per launch vehicle (6,000 if the figure of 6,000,000 parts is correct).

The first alleged live broadcast from the Moon came during prime time hours on Christmas Eve, though I’m sure that was just a chance occurrence. The three astronauts allegedly riding aboard Apollo 8 (Frank Borman, William Anders, and the ever-popular Jim Lovell), in what was billed as a purely spontaneous gesture, took turns reading aloud ten verses from the book of Genesis, which they followed up with: “Good night, good luck, a Merry Christmas and God bless all of you – all of you on the good Earth.” Obviously the Gideon people had thoughtfully left one of their bibles in the capsule sometime before launch.

The impeccable timing of the ‘historic’ Apollo 8 broadcast, reportedly heard by one of every four people on the planet, would set a standard that would be adhered to by all subsequent Apollo flights. The very first Moonwalk by Neil and Buzz was broadcast (‘live’ of course) at 9:00 PM Eastern time, as though it were a Monday Night Football game. Prime time Moonwalks became a staple of the Apollo program, to such an extent that it was not at all uncommon for the networks to be deluged with complaints when a popular weekly sitcom was preempted for yet another fake ‘live’ Moonwalk.

After the second fake Moon landing, NASA began adding exciting new elements to the Apollo missions to combat public apathy. Apollo 13, of course, added the element of danger. Apollo 14 brought us the Moon in Technicolor, with the first color video broadcasts. Apollo 15 kept us entertained with the addition of a Moon buggy. And Apollo 17 featured the first, and only, spectacular night launch of a Saturn V rocket.

Apollo 8 was quickly followed by Apollo 9, which was originally scheduled to lift-off on February 28, 1969, just two short months after the crew of Apollo 8 had splashed down. Luckily, the water in Southern California is a little cold during the winter months and the waves aren’t so good, so the surfers down in Seal Beach were probably able to put in lots of overtime to meet the demanding production schedule.

Apollo 9 was the first Saturn V flight to allegedly have a lunar module stowed away onboard. The mission allegedly featured the first docking maneuvers with, and the very first flight of, a lunar module, albeit in low-Earth orbit rather than in lunar orbit. Apollo 9 was also allegedly the first flight whose crew donned the newly-designed Apollo/Playtex spacesuits.

All things considered, Apollo 9’s ten-day flight in low-Earth orbit was largely a letdown after the previous crew had allegedly flown all the way to the Moon and back (and done so, like true cowboys, without the new magic suits). There was one very odd thing though, never mentioned in the official histories of the space program, that happened during the flight of Apollo 9.

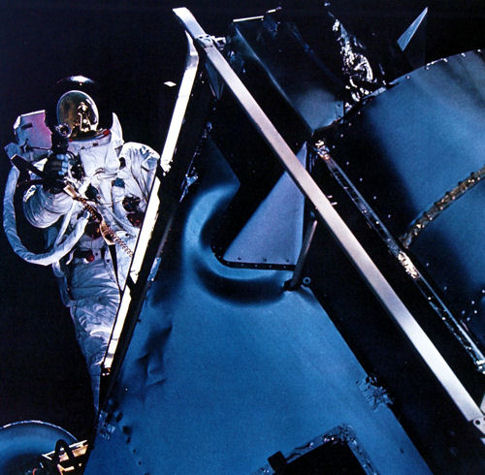

While lounging in the command module, unencumbered by spacesuits, gloves and helmets, and with the luxury of being able to hold their NASA-issue cameras in their hands, the crew (James McDivitt, David Scott, and Rusty Schweickart) took photos of each other that are unfocused, poorly composed, and not particularly well exposed – which is, of course, exactly the results that one would expect from amateur photographers using cameras that lacked viewfinders.

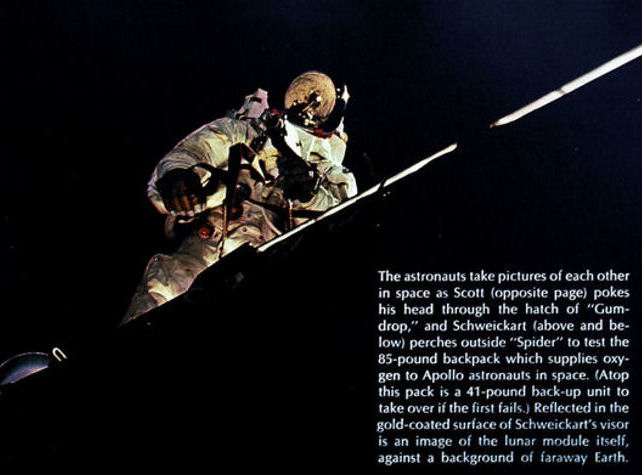

However, after those very same astronauts donned their suits, gloves and helmets, and then ventured out for a spacewalk, making it rather difficult for them to stabilize themselves (and therefore their cameras), something truly wondrous and magical happened: the crew of Apollo 9 suddenly gained the ability to shoot absolutely stunning compositions that look like they were professionally produced in a studio. Though it’s hard to pick a favorite, the one featuring the Earth’s reflection perfectly framed in one of the actor’s helmet visors is pretty impressive.

All of the astronauts on future Apollo missions, of course, proved themselves to be exceptional photographers as well, but only when operating under the most difficult of conditions. Neil Armstrong, the very first photojournalist to allegedly work on the Moon, that most foreign of environments, set the bar exceedingly high for all who were to follow. HJP Arnold, considered to be one of the world’s foremost authorities on space photography before his death in June 2006, once said of the film magazine allegedly shot by Armstrong:

“That sequence of images on the lunar surface, taken mainly by Armstrong of course with that one camera … That film probably I would say has never, ever been bettered, whether on the Moon or subsequently. Almost every one of those relatively small number of images taken by Armstrong appear to be splendidly composed. You remember the classic face-on picture of Aldrin with his visor reflecting the entire landing scene – the lunar module, the flag, the TV camera, and Armstrong taking the picture, uh, reflected in the visor? It’s a marvelous picture!”

Despite all the acclaim he has received for his exploits as an astronaut, Neil Armstrong clearly has been unjustly denied recognition of his astounding abilities as a photographer. Some may argue that he clearly was not playing in the same league as, say, an Ansel Adams, but I beg to differ. Adams created some awe-inspiring work, to be sure, but could he have done so while wearing a spacesuit, gloves and helmet, and with his camera mounted to his chest, and while acclimating himself to an environment that featured no air, greatly reduced gravity, and extreme heat and cold?

I think not.

Speaking of staged photos, by the way, take a look at the photo below, allegedly shot on the Moon by the last men to set foot there, the crew of Apollo 17 (Gene Cernan, Ronald Evans, and Jack Schmitt). It reminds me of something I’ve seen before, possibly some type of a symbol, but I can’t quite place it. (For more fun with Apollo images, drop by Jack White’s site at http://www.aulis.com/jackstudies_index1.html, where you will find a more thorough analysis of photo irregularities than I have seen anywhere else.)

Just two months after the return of Apollo 9, NASA sent Apollo 10 off to the Moon, with Tom Stafford, John Young and Gene Cernan on board. The space agency obviously wanted to get the fake preliminary flights out of the way as quickly as possible so as to get on to the main event. The launch pace would slow considerably once the fake landings began with the next flight, Apollo 11, which blasted off just seven weeks after the return of Apollo 10.

Apollo 10, the third manned launch of a Saturn V, once again allegedly went to the Moon, this time with a lunar module mounted to the nose of the command module. The Apollo 10 mission allegedly included everything that later missions would experience short of actually landing on the lunar surface. Once allegedly in lunar orbit, the lunar module was deployed and flown down fairly close to the surface, before returning to and successfully docking with the command and service modules.

Having endured the perilous initial launch, and then the quarter-million-mile flight to the Moon, followed by the successful deployment and flight of the LEM, and having gotten to within pissing distance of being the first men to create those historic first footprints on the Moon, it would naturally have been tempting to ignore mission control and set down for a quick stroll into history. To prevent this, according to the official mythology, NASA diabolically short-fueled the LEM for the Apollo 10 mission.

There was, of course, no possibility that some unforeseen circumstances might have necessitated the use of that additional fuel, or necessitated a landing on the Moon, which would have been a bit of a PR nightmare for the agency. Walter Cronkite would have had to break the news to the American people: “The crew of Apollo 10 unexpectedly became the first men to set foot on the Moon just moments ago, and we have been promised live footage momentarily. Unfortunately, their spacecraft was deliberately short-fueled so they will not be able to make the return flight to dock with the mothership and both astronauts will soon die. This should make for some riveting TV though, so stay tuned.”

The last of the major Apollo contracts to be awarded was for the ever-popular lunar rovers, aka Moon buggies. The initial idea for a lunar vehicle is generally credited to Walt Disney’s favorite Nazi, Wernher von Braun, who envisioned a mobile, pressurized lab weighing some four tons, capable of carrying enough provisions to keep two astronauts alive for up to two weeks. The concept, dubbed MoLab, would have required the launch of a separate Saturn V rocket, so the idea was dropped as being too expensive (although NASA seems to have had a virtually inexhaustible supply of Saturn Vs; when the Apollo program was scrubbed, NASA already had all the hardware built for flights 18, 19 and 20 – and had the crews trained as well.)

NASA supposedly gave up entirely on the idea of placing a vehicle on the Moon, but General Motors’ Defense Research Laboratories purportedly soldiered on, putting the company’s own money into research and development of the vehicle. As the story goes, NASA told the team at GM that if they could somehow come up with a way of fitting an operational vehicle into an impossibly small lunar module equipment bay, the agency might consider incorporating the vehicle into future Apollo missions.

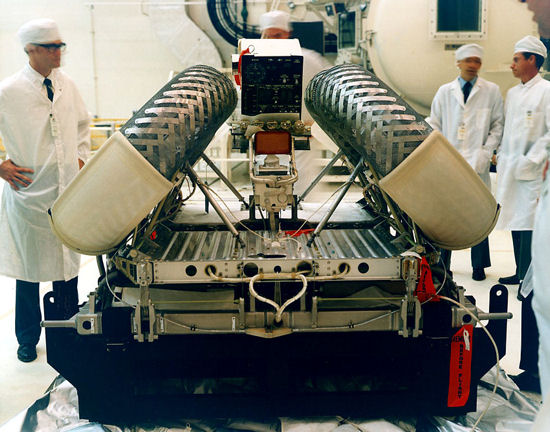

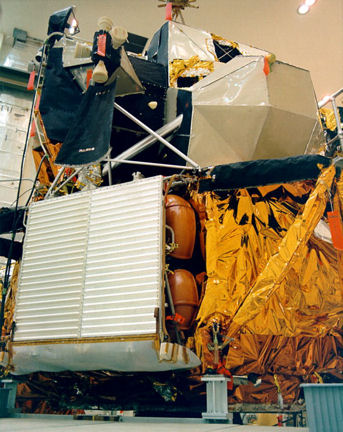

Speaking of the lunar modules, by the way, I happened to stumble across the photo below of the LEM’s mighty descent engine, which, as can be clearly seen, would have hardly taken up any room at all in the spacious spacecraft’s descent stage. Its fuel tanks wouldn’t have required much space either, so there should have been plenty of room left to stow a folding dune buggy in a curiously empty equipment bay.

Below is a NASA-approved image of the rover folded up and ready to pack into its assigned equipment bay, along with a photo of the folded rover allegedly stowed away on a LEM that has clearly seen better days. And here is a brief video clip of the deployment of the folded rover being demonstrated, presumably at the manufacturing plant.

As can be clearly seen, particularly in the video clip, the rover, as initially deployed, was far from complete. It seems to be missing such things as a floor pan, and seats, and cameras, and antennae, and battery packs, and various other components – which raises a few questions, such as where were all the other rover parts stowed? How many empty equipment bays were available to accommodate all the various rover components? And how long exactly did it take the astronauts, given the limitations imposed by their suits and gloves, to deploy and fully assemble a Moon buggy?

GM’s crafty R&D team, led by project manager Sam Romano and chief engineer Ferenc Pavlics, supposedly came up with the innovative folding rover concept in less than a month, and, in July of 1969, as Armstrong and Aldrin were allegedly taking man’s first steps on the Moon, GM was awarded the contract to design and build the rovers. GM quickly teamed with Boeing and got to work, with two significant challenges to overcome – the rover must fit into the assigned bay, and the total weight was to be kept to a maximum of 400 pounds. Also, the team had to move from concept drawings to mission-ready rover in just 17 months.

As with all other aspects of the Apollo program, those lofty goals proved surprisingly easy to achieve. By early 1971, GM and Boeing had already delivered their first mission-ready rover to NASA for final testing and approval. On July 31, 1971, just two years after the contract had been awarded, what remains to this day the only manned vehicle to allegedly land on an extraterrestrial body began kicking up Moon dust.

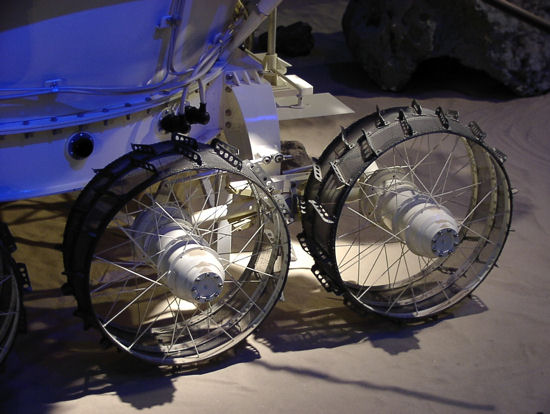

The finished product looked not unlike an Earth-based dune buggy, albeit with the unique ability to neatly fold away. The vehicle featured simultaneous front and rear steering and steel-mesh tires mounted on wheels that were each driven by their own separate motors. Power was supposedly provided by an array of batteries mounted on the front end of the rover.

Since no one really knew what kind of a vehicle would be required to drive on the Moon, early conceptual rovers ran the gamut from vehicles with massively oversized wheels to those propelled by tank-like tracks to Archimedean screws that would be able to burrow through the lunar dust like mechanical moles. Luckily, through extensive research and development, the Apollo team was able to deduce exactly which design components would allow the rovers to operate with maximum efficiency on the lunar terrain.

Or so the story goes. In reality, the rover team obviously had no time to do much at all in the way of research, development and testing. The Soviets, on the other hand, took the development of their Moon vehicle very seriously – seriously enough to spend an entire decade researching, developing and relentlessly fine-tuning every aspect of their robotic rover.

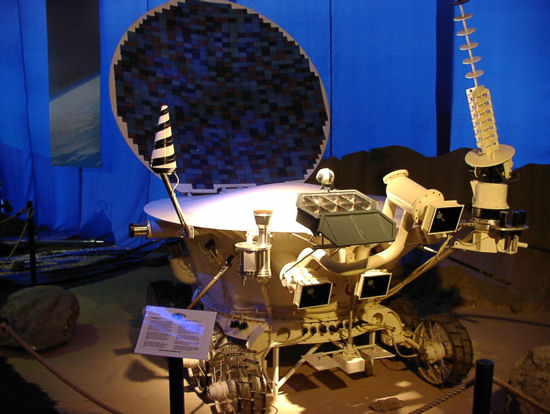

Dubbed the Lunokhod (the English translation of which is “Michael Jackson” … err, wait a minute, make that “Moonwalker”), the Soviet rover was an engineering marvel that was outfitted with an array of both still and television cameras as well as a wide assortment of testing equipment, including an X-ray spectrometer, an X-ray telescope, soil testing instruments, an astrophotometer, a laser retroreflector, a fluorescence spectrometer, and a magnetometer.

Lunokhod II, deployed in January of 1973, some thirty-seven years ago, to this day holds the record for having traversed further on an extraterrestrial body (about 23 miles) than any other robotic rover – considerably further than America’s two Mars Pathfinder vehicles combined.

So serious were the Soviets about testing their rover that, in the summer of 1968, they built a secret Lunodrom (Moondrome) in the remote village of Shkolnoye. Spanning some two acres, the Moondrome featured craters up to 50 feet in diameter and fake lunar rocks of all shapes and sizes. It would have been, needless to say, an excellent place to create fake Moon photos and television footage – though conventional wisdom, of course, holds that Soviet scientists and American scientists didn’t play well together in those days.

It’s hard though not to conclude that NASA basically appropriated the lunar rover research done by the Soviets as their own. According to a French documentary (Tank on the Moon), the Soviets did indeed spend many long years researching all the various means of locomotion that NASA claimed to study as well. And after doing so, Russian engineers (led by Alexander Kemurdjian, who NASA later consulted with on its Pathfinder project) came up with many of the same key design elements that would be utilized on NASA’s lunar rovers, such as the mesh tires and the independently powered wheels.

The Lunokhod vehicles had eight wheels, each with its own independent motor, suspension and brake. The rovers were ‘driven’ by a five-man team here on planet Earth, using panoramic images beamed back in real-time to guide the robotic vehicles. The design team had developed a special lubricant that would perform in a vacuum and they had enclosed each wheel motor in a pressurized housing. The vehicle’s batteries recharged via a collection of solar cells on the inside of the craft’s lid, which was kept open during the lunar day. During the frigid lunar night, the rover hibernated, kept warm by an internal radioactive heat source.

Lunokhod I set down on the Moon on November 17, 1970, just a few months before NASA took possession of the first mission-ready lunar rover. When that first rover allegedly arrived on the Moon eight months later, in July of 1971, Lunokhod I was still traversing the lunar landscape.

No comments:

Post a Comment