“The LEM (Lunar Excursion Module) was coated in Mylar. To many engineers, the final vehicle was an insult to every notion of what a spacecraft should look like … It was one of the weirdest and most improbable flying machines ever conceived.” – Moon Machines: The Lunar Module, Science Channel, 2008

While idly flipping through the channels the other day, I noticed that the Science Channel was planning to air a couple of Moon landing documentaries. Luckily, I was a bit bored that day so I decided to tune in, though I was not really expecting much beyond the standard claims that have been made in numerous other documentary films focusing on the alleged Apollo missions.

I was pleasantly surprised, however, to find that the two hours that I spent watching the Science Channel spin the Moon landings was time well spent, seeing as how I picked up quite a few facts that I had not previously come across in other source material. The most important thing that I learned was a lesson, of sorts: never attempt to mock the Apollo missions – for the simple reason that all such efforts will be in vain, since no claim made in jest, no matter how absurd, can ever top the lunacy of actual claims made by NASA and its subsidiaries.

The better of the two televised documentaries was Moon Machines: The Lunar Module, which turned out to be part of a series which, as luck would have it, is readily available on Netflix (with all six hours conveniently packaged on a single DVD). Netflix seemed to think that I might also enjoy Nova’s two-hour To the Moon and the Discovery Channel’s multi-part When We Left Earth, so I added those to my queue as well. Having now absorbed everything that Moon Machines, To the Moon, When We Left Earth and First on the Moon: The Untold Story have to offer, I realize that my debunking of the alleged Moon landings wasn’t really as thorough as it could have been, so another chapter is on order. Or maybe two. Or possibly three. Perhaps even four.

Moon Machines: The Lunar Module began by having a talking-head named Josh Stoff explain to viewers that when JFK delivered his historic speech on May 25 of 1961 – the one in which he boldly proclaimed that Americans would walk on the Moon by the close of the decade – “The United States had a total of fifteen minutes of space flight experience … and now we were committed to go to the Moon … We knew nothing about the Moon.”

Indeed, if Kennedy had delivered that speech just three weeks earlier, Stoff’s statement would have to be modified to: “The United States had no space flight experience at all, and now we were committed to going to the Moon!” On May 5, 1961, Alan Shepard had become the first American in space when he took a 15-minute ride in a Mercury capsule that basically went up and then came right back down. That mission was a hastily assembled “Hey, look! We can do it too!” response to the USSR having put the first man in space on April 12, 1961.

Shepard’s accomplishment didn’t even come close to what the Soviets had achieved. Yuri Gagarin had ridden the Vostok 1 into low-Earth orbit, completing a single orbit in 1 hour and 48 minutes. In comparison, Shepard had essentially taken a short ride aboard an oversized bottle-rocket. It would take another four months, until September 13, 1961, for the United States to get its first unmanned spacecraft to complete an Earth orbit. It would not be until near the end of February 1962, nearly a year after Gagarin’s flight, that NASA would claim to have gotten an American (John Glenn) into orbit.

On the day of Gagarin’s historic flight, a clearly uncomfortable President Kennedy fielded questions from a concerned press corps. Asked if we intended to beat the Russians to the Moon, Kennedy testily replied that “we first have to make a judgment, based on the best information we can get, whether we can be ahead of the Russians to the Moon.” Asked a follow-up question about the Saturn rockets already under development by the von Braun team, an obviously annoyed Kennedy replied that “Saturn is still going to put us well behind.”

Konrad Dannenberg, a rocket propulsion engineer who worked alongside von Braun for some 33 years, first in Nazi Germany and then in Huntsville, Alabama, readily agreed that “They [the Soviets] were really in all areas way ahead of us.” So despite the frequent claims of ‘debunkers’ that it was actually a close race, or that the Soviets weren’t really leading at all, everyone from the President to the scientists who actually designed and built the machines that allegedly took us to the Moon agreed at the time that the Soviets were far ahead of the U.S. in virtually all aspects of the space race.

The ‘debunkers’ are right about one thing though: the list of Soviet firsts that I included in an earlier post in this series is not entirely accurate. Truth be told, I appear to have sold the Soviets short by leaving out a number of the early accomplishments of their space program, including a couple of firsts that the United States was unable to match for decades. Here then is a more complete list of Russian firsts in the years leading up to and during the alleged Apollo missions:

May 15, 1957 – The Soviet Union tests the R-7 Semyorka, the world’s first intercontinental ballistic missile.

October 4, 1957 – The Soviets launch Sputnik 1, Earth’s first manmade satellite.

November 3, 1957 – A dog named Laika becomes the first animal to enter Earth orbit aboard Sputnik 2. Unfortunately for Laika though, she isn’t booked for a return flight.

January 2, 1959 – Luna 1 becomes the first manmade object to leave Earth’s orbit.

September 13, 1959 – After an intentional crash landing, Luna 2 becomes the first manmade object on the Moon.

October 6, 1959 – Luna 3 provides mankind with its first look at the far side of the Moon.

August 20, 1960 – Belka and Strelka, aboard Sputnik 5, are the first animals to safely return from Earth orbit.

October 14, 1960 – Marsnik 1, the first probe sent from Earth to Mars, blasts off.

February 12, 1961 – Venera 1, the first probe sent from Earth to Venus, blasts off.

April 12, 1961 – Yuri Gagarin, riding aboard the Vostok 1, becomes the first man in Earth orbit.

May 19, 1961 – Venera 1 performs the first ever fly-by of another planet (Venus).

August 6, 1961 – Gherman Titov, aboard the Vostok 2, becomes the first man to spend over a day in space and the first to sleep in Earth orbit.

August 11 & 12, 1962 – Vostok 3 and Vostok 4 are launched, the first simultaneous manned space flights (though they do not rendezvous).

October 12, 1964 – Voskhod 1, carrying the world’s first multi-man crew, is launched.

March 18, 1965 – Aleksei Leonov, riding aboard the Voskhod 2, performs the first space-walk.

February 3, 1966 – Luna 9 becomes the first probe to make a controlled, ‘soft’ landing on the Moon.

March 1, 1966 – Venera 3, launched November 16, 1965, becomes the first probe to impact another planet (Venus).

April 3, 1966 – Luna 10 becomes the first manmade lunar satellite.

October 30, 1967 – Cosmos 186 and Cosmos 188 become the first unmanned spacecraft to rendezvous and dock in Earth orbit. The United States will not duplicate this maneuver for nearly four decades.

January 16, 1969 – Soyuz 4 and Soyuz 5 become the first manned spacecraft to dock in Earth orbit and the first to exchange crews.

November 17, 1970 – Lunokhod 1, the first robotic rover to land on and explore an extraterrestrial body, lands on the Moon. Twenty-seven years later, the United States lands it’s very first robotic rover on Mars.

December 15, 1970 – Venera 7 becomes the first probe to make a soft landing on another planet (Venus).

April 19, 1971 – Salyut 1 becomes the world’s first orbiting space station.

August 22, 1972 – Mars 2 becomes the first probe to reach the surface of Mars.

I feel much better now that we have set the record straight on all of that. And I’m sure that the ‘debunkers,’ who in the past have described much shorter lists of Soviet firsts as ‘padded,’ will feel much better as well.

The Soviets achieved the first fly-by of the Moon, launched the first craft to impact the Moon, were the first to make a soft landing on the Moon, put the first object into lunar orbit, and remain, to this day, the only nation to land and operate a robotic vehicle on the Moon. It should now make perfect sense to everyone then why the Soviets, who were ahead of us in virtually all aspects of space exploration, in some cases by decades, never landed a man on the Moon. Or even sent a man to orbit the Moon. Come to think of it, they never even sent a dog to the Moon.

It would be difficult to argue that the Russians didn’t have adequate funding for their space program, or that they didn’t have some of the finest scientific minds on the planet working for that space program, or that they didn’t have the will and desire to succeed. What they were lacking, I’m thinking, is access to Hollywood production facilities. Returning then to our prior topic of discussion …

On April 14, 1961, two days after Gagarin’s historic flight, a panicked Kennedy reportedly inquired of NASA what goal in space we might be able to attain before the Soviets. According to legend, Kennedy was told that America’s best hope to beat the Russians was with a manned Moon landing. The reasoning was that the Soviets were so far ahead of us that they would surely trounce us in achieving any milestones attainable in Earth orbit (space-walks, prolonged flight, rendezvous and docking maneuvers, etc.), so our best bet was to shoot for a far-off goal.

The problem, however, was that none of the technology required to attain such a goal existed at that time. We did not have the rocket technology to power such a mission, nor the navigation system to guide such a journey, nor the digital computer technology to control that navigation system, nor the spacesuit technology to protect our astronauts, nor the technology to rendezvous or dock in space, nor the technology to create a dune buggy capable of operating on the Moon, nor the technology to design and create a lunar landing vehicle. NASA had been in existence for less than three years, having been created in 1958 as a direct response to the USSR’s launch of Sputnik.

Nevertheless, just eight summers later, we allegedly did indeed land men on the Moon. In just eight short years, starting essentially from scratch, we designed, built, tested, refined and perfected every piece of technology required to put men on the Moon, and we did it so well in that brief period of time that by July of 1969, every cog in the wheel performed nearly flawlessly. And yet now, with a half-century of space exploration now under our belts, and with all the necessary technology long perfected, NASA advises us that it would take twice as long to put a man on the Moon. But I may have already pointed that out.

Following Kennedy’s bold declaration, nobody really had any clue how to get astronauts to the Moon and back. One school of thought held that what was needed was a humongous rocket ship that would fly all the way there, land, and then fly all the way back. The main drawback to this proposal was that it was completely preposterous. The biggest problem was that it would require somehow landing a 300-foot tall cylinder in a perfectly upright position. But that wasn’t the only problem. Getting in and out of a capsule mounted atop a tall rocket ship can be a bit of a problem as well. And re-launching that rocket without a launch pad and ground crew can be a real bitch.

Another idea called for the launch of two large rocket ships, one primarily carrying fuel and the other carrying our fearless astronauts. The idea was that the two vehicles would rendezvous and dock in Earth orbit, the manned ship would refuel from the other ship, and our boys would then leave for the Moon. Why this was deemed necessary is anyone’s guess, given that the ‘debunkers’ generally claim that you don’t really need much fuel once you leave Earth orbit since you just kind of fall through the vacuum of space until you get to the Moon.

Amidst all the preposterous ideas on how to get our guys to the Moon ahead of the Russkies, one lone voice in the wilderness, an “obscure engineer” by the name of John Houbolt, had been promoting a radically different plan: build a second lightweight spacecraft, to be carried aboard the larger mother ship, that would be capable of shuttling down to the Moon and back while the larger ship remained in lunar orbit!

As Moon Machine’s narrator solemnly intoned, “There was only one massive drawback: to get back to Earth would require the lunar shuttle to rendezvous with the mother ship in lunar orbit.” As Stoff added, “What scared everybody about it was you had to rendezvous and dock around the Moon. You’re a quarter of a million miles from Earth! And he’s proposing this in 1961, when we had no space flight experience and just rendezvousing in Earth orbit concerned everybody.”

Needless to say, everyone scoffed at Houbolt’s radical suggestion. The very vocal opposition at NASA was led by Mr. von Braun, who categorically and heatedly dismissed the notion of completing a lunar orbit rendezvous (the idea, by the way, appears to have been cribbed from an early Soviet study). But Houbolt was allegedly a tenacious sort who wasn’t about to give up easily, even going so far as to write directly to Bob Seamans at the top of the NASA food chain on November 15, 1961. Houbolt was, of course, immediately taken seriously by the NASA brass, who promptly decreed that his ideas should get a serious hearing.

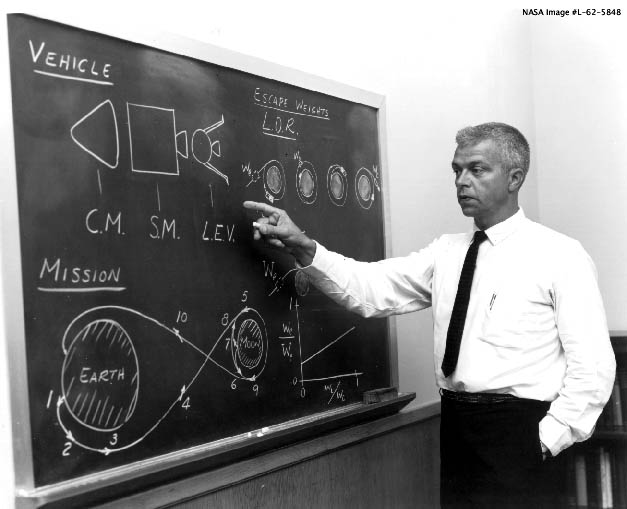

A major turning point was supposedly reached when a meeting was convened in June of 1962. During that historic meeting, we are informed by the narrator of Moon Machines, “von Braun took everybody by surprise.” Wernher’s own team gave a detailed presentation to the assembled scientists, after which von Braun thanked and profusely complimented them – before telling them that he was going to recommend that NASA not go with his own team’s concept. Instead, he was going to recommend the so-called LRO, or lunar orbit rendezvous, option!

As yet another authoritative talking-head named Bill Causey explained, “It was such a surprise to everybody that even his own staff people, several days later, had a private meeting with him and they said, ‘Why in the world did you say that?’” Why indeed? My guess is that someone finally passed Wernher the memo explaining that he needed to get over the silly notion that the plan was to actually go to the Moon. What was needed, instead, was a plan that could be feasibly sold to the American people.

Curiously, Mr. Houbolt, who we are led to believe was single-handedly responsible for selling NASA on the lunar module concept, and without whom we would have probably never allegedly sent men to the Moon at all, has been all but forgotten. That seems a rather strange way for history to treat the man whose brilliant mind allegedly opened the door for man to walk on the Moon.

The man whose name is most commonly referenced when discussing the lunar module, by the way, is a gent by the name of Thomas Kelly, who served as the project manager for the design, construction and testing of the LEM. Kelly happened to be a member of the Quill and Dagger Society, Cornell University’s answer to Yale University’s notorious Skull and Bones. I just thought maybe I should mention that.

In July of 1962, NASA announced that it was fully committed to the lunar shuttle concept and began shopping around for a contractor to build it. As fate would have it, a small aircraft company on Long Island, the Grumman Corporation, had already been working on the design of an independent lunar shuttle vehicle, cleverly anticipating the market demand. Grumman thus was able to submit a much more detailed proposal than other competitors, sealing the deal with NASA.

In November of 1962, Grumman was awarded the contract to build what Moon Machines described as “the most complicated and sophisticated spacecraft ever conceived.” Soon after, we are also informed that the LEM was “what many regarded as the first true spaceship.” In other words, America’s “first true spaceship” was also America’s “most complicated and sophisticated spacecraft.” To this day, no other spacecraft has been built that is capable of landing men on a planetary body. To this day, no other spacecraft has been built that is capable of taking off from and flying home from a planetary body. To this day, no other spacecraft has been built that is capable of performing rendezvous and docking maneuvers in lunar orbit. To this day, no spacecraft has been built that can protect astronauts from the hazards of flying through space outside of the Van Allen belts.

When you think about it, of course, it makes perfect sense that America’s first true spacecraft, coming as it did during the infancy of the Space Age, would also stand to this day as the most complicated and sophisticated spacecraft “ever conceived.” After all, didn’t Henry Ford build the most complicated and sophisticated automobile ever conceived? And didn’t Orville and Wilbur build the most complicated and sophisticated aircraft ever conceived? And didn’t Alexander Graham Bell invent the IPhone?

From the outset, Grumman envisioned a two-stage vehicle, with as much of the weight as possible carried in the lower half, or descent stage, of the spacecraft. Eliminating excess weight was of paramount importance. Early designs included no ladder, for example, as a ladder was considered unnecessary weight. In 1/6 gravity, it was assumed, the astronauts would be able to climb in and out of the capsule using just a rope. Of course, the modules never came anywhere close to being in a reduced gravity environment, which is probably why a ladder was added to the landing vehicle.

According to the Science Channel, the only constant in Grumman’s drive to design the modules was change. So much so that, “Finally, in the spring of 1965, NASA, worried design changes would never stop, imposed a freeze.” NASA had apparently decided that two-and-a-half years, working with the knowledge and technology of the early 1960s, was plenty of time to design the “most complicated and sophisticated spacecraft ever conceived.” Whatever the Grumman team had come up with to that point would have to be good enough to get our flyboys from the mother ship to the Moon and back.

It was now time to go to work actually building what was described as “an entirely independent spacecraft, with its own motors, fuel, life support system and navigation equipment. To some at the time, it seemed excessive.” To many others at the time, it just seemed ridiculous.

I happened to stumble across, by the way, an image depicting a 1963-era LEM prototype parked on the surface of the Moon. As has been the case throughout this series, the image comes directly from NASA’s web pages, where it was proudly presented as the “Image of the Day.” It shouldn’t be too hard to figure out what it is that I love about this image – even if it does prove me to be a liar, given that I previously claimed that none of NASA’s Moon photos depict any stars in the lunar sky.

According to the folks at the Science Channel, the lunar module “was built in one of the world’s first clean-rooms. In zero gravity, any floating foreign body would be a hazard.” A hazard, that is, to both the astronauts’ health and to the ship’s delicate on-board electronics. Workers were required to wear gowns, masks, hairnets and booties, technicians meticulously cleaned the interior with camel hair brushes and filter paper, and the modules were robotically lifted, inverted and shaken to rid the cabin of any debris.

Although the narrator forgot to mention it, I’m pretty sure that the astronauts were also instructed not to shed any hair or skin during the missions. On a more serious note, NASA did, in fact, reportedly consider requiring the astronauts to shave from head to toe. That never happened, of course, probably due to the fact that hairless and eyebrow-less astronauts wouldn’t have been as warmly embraced by the American public, and the Apollo missions were more about appearances than they were about science.

Left unexplored by the makers of Moon Machines was the obvious question of how those clean-room conditions could have been maintained once the lander set down on the Moon. The astronauts couldn’t shed their protective suits until they were back in the safety of the pressurized capsule, so how exactly did they keep from tracking copious amounts of that lunar dust back into the allegedly sterile LEM cabin? As is revealed in the Lunar Rover episode of the Moon Machines series, “The astronauts quickly learned that the dust adhered to everything it touched.”

Everything, that is, except the outside of the lunar module, which, as we have already seen, remained as clean as if it were sitting on the showroom floor. And the dust apparently also didn’t adhere to the astronauts’ boots or spacesuits, even if Apollo astronaut Charlie Duke did say, while describing what it was like to ride in the lunar rover, that “Moon dust was pouring down on us like rain, and so after a half of a Moon walk, our white suits turned gray.” None of that dust, of course, was introduced into the sterile interior of the cabin.

We know that with absolute certainty because we have already been told that in order for the lunar module to operate safely and correctly, the cabin had to be kept dust-free. One of the best-kept secrets of the Apollo program, it turns out, is that there was actually a third passenger along for the rides to the Moon and back: Neil Armstrong’s mother. Her primary responsibility was to make sure the boys properly wiped their feet before entering the capsule.

Astute readers, by the way, may have noticed that Duke’s comments about driving the rover directly contradict another of the fables sold by the ‘debunkers.’ According to Phil Plait, if you watch the video footage allegedly shot on the Moon, “you will see dust thrown up by the wheels of the rover. The dust goes up in a perfect parabolic arc and falls back down to the surface. Again, the Moon isn’t the Earth! If this were filmed on the Earth, which has air, the dust would have billowed up around the wheel and floated over the surface. This clearly does not happen in the video clips; the dust goes up and right back down. It’s actually a beautiful demonstration of ballistic flight in a vacuum.”

As would be expected, we find Jay Windley making essentially the same claim: “dust will fall immediately to the lunar surface. The behavior of the dust in the video and film taken on the lunar surface is one of the most compelling reasons we have for believing it was shot in a vacuum. The dust is clearly dry, but it falls immediately to the surface and does not form clouds.”

Who then are we to believe? The guy who actually operated the rover, allegedly on the surface of the Moon, and said that the dust was raining down on he and his partner from all directions, or a couple of self-proclaimed ‘experts’ who directly contradict NASA’s man-on-the-scene?

There is a reason, I might add here, why NASA defers to these two clowns while not officially endorsing their ‘debunking’ arguments. It’s called plausible deniability. NASA knows that ‘debunking’ the fact that the Moon landings were hoaxed requires a lot of twisting of facts and the promotion of a lot of dubious science, and they choose not to be directly involved in such endeavors. That is also, no doubt, why the agency withdrew its sponsorship of a ‘debunking’ book that is said to be in the works.

No comments:

Post a Comment